|

As the number of cases — and, sadly, the number of deaths — continue to increase, we’re extending another thank you to all of the selfless, compassionate people helping to take care of everyone during these strange, unprecedented times.

All of us can help keep our front-line heroes and everyone else safe, including ourselves, by wearing a face mask. It’s a small, yet responsible, act to show our concern and compassion for people. According to the CDC, this will help prevent the spread of Covid-19, especially because some can have the disease but not show any symptoms, and the disease spreads via coughing, sneezing, and talking. Stay safe, everyone, and help keep others safe too!

0 Comments

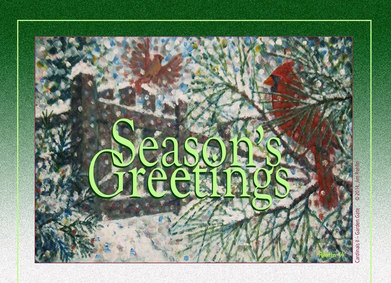

Wishing the best of the season to you and your loved ones, with peace and happiness now and throughout the new year!

Cardinals / Garden Gate, 28” x 18” acrylic-on-canvas painting by Jim Rehlin Joan M. Rehlin

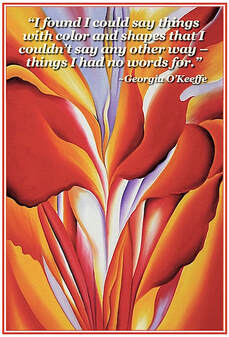

We’re highlighting Georgia Totto O’Keeffe (11/15/1887–3/6/1986) in this mini art history post. An American artist who is considered the Mother of American modernism, O’Keeffe decided at age 10 that she wanted to be an artist. After receiving her first art instruction from a watercolorist in her hometown of Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, in 1905 O’Keeffe attended the Art Institute of Chicago. Then in 1907 she studied at the Art Students League in New York City, but O’Keefe felt constrained by her lessons there, which taught students to copy scenes in nature. While in New York City, O’Keeffe visited galleries such as 291, and met its co-owner Alfred Stieglitz. When her finances ran out, O’Keeffe worked as a commercial illustrator, 1909–’10. Then from 1911–’18, she taught in Virginia, Texas, and South Carolina. During that time, O’Keefe was introduced to the principles of creating works of art based on interpretation of subjects, rather than an attempt to copy them, and this caused a major shift in O’Keefe’s approach to art. In 1917, art dealer and photographer Stieglitz held an exhibition of O’Keefe’s work, and at his request, she moved to New York to focus seriously on her art. Stieglitz provided financial support plus a New York residence and studio for O’Keefe. They developed a close professional as well as personal relationship which led to their marriage in 1924, and they lived together in New York until 1929. O'Keeffe then spent part of each year in the Southwest until Stieglitz, who was 23 years her senior, passed. At that point, O’Keefe lived permanently in New Mexico at the Georgia O’Keeffe Home and Studio in Abiquiu until the last several years of her life when she lived in Santa Fe. By the mid-1920s O’Keeffe became well-known for her close-up paintings of natural objects. She painted about 200 large-scale flower images which appear to be viewed through a magnifying lens, and she’s quoted as saying: “I’ll paint what the flower is to me. I’ll paint it big and they’ll be surprised into taking the time to look at it.” She also created abstract art of New Mexico landscapes and New York skylines, and her work has been exhibited in New York and other locations. During the 1940s, she had two, one-woman retrospectives. The first was at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1943; the second, in 1946 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in Manhattan where O’Keefe was the first woman to have a retrospective. A popular artist who received a number of commissions, O’Keeffe holds the record for the highest price paid for a painting by a woman when, on November 20, 2014, her Jimson Weed sold for $44,405,000. Red Canna (shown here), which is one of O’Keefe’s flower paintings, is currently owned by Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas. Red Canna 1924, oil, Georgia O’Keefe Joan M. Rehlin

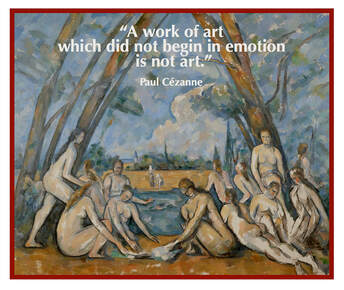

This mini art history post highlights French artist Paul Cézanne (1/19/1839–10/22/1906). Identified with Post-Impressionism, his work influenced the transition from late 19th century artwork to a fundamentally different type of art in the 20th century, including Cubism. Cézanne treated nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone, and his paintings represent an architectural style with simple forms and planes of color to depict the world as he saw it. Born in Aix-en-Provence, Cézanne was a beneficiary of his father’s financial success, resulting in a comfortable lifestyle that was unavailable to most of Cézanne’s contemporaries. At 18 he attended the School of Drawing in Aix and then, at his father’s request, the University of Aix Law School. He studied drawing in both schools and, at 22, was encouraged by his friend Émile Zola to move to Paris to pursue his artistic development. In the 1880s, Cézanne returned to his beloved Provence in the south of France. He painted landscapes, portraits, still lifes, and various studies of bathers which are notable due to the lack of nude models. Beginning in 1863, Cézanne’s art submissions were rejected over and over by the jury of the Salon, which was the official exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Cézanne’s rejected paintings were instead accepted by the Salon des Refusés, which displayed art unaccepted by the Salon. Finally, due to fellow artist Antoine Guillemet’s intervention, Cézanne had three paintings accepted for exhibition in the Salon in 1882. He also exhibited at the first and third Impressionists exhibitions, 1874 and 1877, and in several other venues. In 1895 he had his first solo exhibition, presented by Ambroise Vollard, an important Parisian dealer. Although he attracted the attention of dealers and art collectors whose commissions provided additional financial support, Cézanne’s work was often ridiculed, not understood, and not well-received by established galleries and the general public. Despite those early rejections, in his later years Cézanne’s paintings became sought after, and his work earned respect from the younger generation of painters, including Picasso. Cézanne’s artwork with geometric and optical artistic exploration influenced those artists to experiment with the fractured form, which became known as Cubism. Although afflicted by health problems, Cézanne continued to paint the last few years of his life. In the fall of the year following his death, Cézanne’s paintings were exhibited in a large retrospective at the renowned Salon in Paris, which confirmed his standing as one of the most influential artists of the 19th century. Among Cézanne’s series of Bathers paintings is Les Grandes Baigneuses (The Large Bathers 82.8" x 98.7"), shown here, which is hanging in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Les Grandes Baigneuses, 1905, oil on canvas, Paul Cézanne Joan M. Rehlin

We’re highlighting John Constable (6/11/1776–3/31/1837) in this mini art history post. Constable was an English artist, known for his naturalistic landscape paintings of Dedham Vale, Suffolk, the area surrounding his home which he loved. Constable attended classes at the Royal Academy Schools in 1799, studying old masters. Refusing a position as drawing master at Great Marlow Military College in 1802, he focused instead on becoming a professional landscape painter. In 1803, he began exhibiting paintings at the Royal Academy and, for inspiration, took a two-month tour of England’s Lake District in 1806. In 1819, he sold his first major painting, The White Horse, and was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy. In 1821, Constable’s The Hay Wain, on exhibit at the Royal Academy, led to its purchase along with three more of his paintings by an art dealer, John Arrowsmith. Arrowsmith then exhibited The Hay Wain at the Paris Salon in 1824, where it won a gold medal. Constable was elected to the Royal Academy in 1829, and in 1831 was appointed Visitor at the Royal Academy where he was popular with the students. Constable sold more of his work in France than his native England, and was also a leading inspiration for the Barbizon school, a mid 19th century school of French landscape painters, who were against the classical conventions and based their art on the study of nature. He believed that “painting is but another word for feeling.” Although his paintings are now among the most popular and valuable in British art, Constable was never financially successful. Also, his personal life was difficult due in part to his in-laws who threatened to disinherit their daughter when she married Constable because they believed his family was beneath theirs. Constable’s beloved wife, Maria, bore seven children, but died shortly after the last one was born. Her death left Constable to raise them all on his own, on his meager earnings. As an example of his landscape work, we’ve included Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop’s Garden (below), which Constable painted for John Fisher, the Bishop of Salisbury who commissioned this work. As a gesture of appreciation, Constable included the Bishop and his wife at the bottom left of the painting, under the trees. This painting is currently in the Frick Collection, New York City. Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop's Garden, c.1825, oil on canvas, John Constable The focus of this year’s Earth Day is on the protection of our many endangered and threatened species, including insects which provide countless benefits to our earth.

One benefit is that Insects pollinate most of our plants and flowers, which helps provide a stable source of food for humans and other living creatures. Without insects our global ecosystems would collapse, but due to habitat loss, climate change, and pesticide use the insect population has already declined 45% during the past four decades. The good news is, it’s not too late to change this pattern of loss and protect our insects… and our earth. One suggestion is to stop pesticide and herbicide use in our own yards. Visit Earth Day Tips for more about what we as individuals can do. And visit Earth Day 2019 for general details.. A fun bug fact: Dragonflies have been on earth more than 300 million years. In recognition of this year’s Earth Day theme, we’re highlighting Jim Rehlin’s Hosta / Dragonfly 20" x 20" acrylic-on-canvas). We chose this painting because, this morning, Jim saw the first gossamer-winged dragonfly to visit us during the 2019 season. To view all of Jim’s artwork, some of which contain other hidden insect surprises — bee, ladybug, praying mantis, and more — visit our Online Galleries. And please send Jim a message via the email icon, above right, if you have questions or are interested in purchasing any of his art. Joan M. Rehlin

Our mini art history post highlights Helen Beatrix Potter (7/28/1866–12/22/1943) who was not only a well-known English writer of children’s books, but also an accomplished illustrator, natural scientist, and conservationist. Born in London to upper-class parents, Potter spent a privileged but isolated childhood. She was taught at home by a series of governesses, and spent family holidays in Scotland and in England’s Lake District where she developed a love of plants and animals. During childhood, she and her brother Bertram kept numerous small animals as pets — mice, rabbits, a hedgehog, and some bats — which they observed closely and drew endlessly. Potter’s artistic and literary talents were also influenced by her fascination with fantasy books and fairy tales. And as a teenager, she visited numerous London art galleries. Although Potter was aware of artistic trends, her style was uniquely her own. Potter often wrote letters that included sketches of animals and landscapes. She was eventually encouraged by Annie Moore, one of her governesses, to create children’s books when she wrote an illustrated letter to Moore’s son about four little rabbits whose names were “Flopsy, Mopsy, Cottontail, and Peter.” This, of course, evolved into The Tale of Peter Rabbit, one of the most famous children's stories ever written. Potter initially self-published it in 1901. When it sold out, it was published the following year by Frederick Warne & Co. Gaining immediate success, Potter went on to write, as well as illustrate, 22 additional Tales plus several other books. She was also an astute businesswoman who made and patented a Peter Rabbit doll shortly after the book was published, along with other spin-off merchandise including figurines, wallpaper, painting books, and porcelain tea sets. Potter’s popularity was based on her imaginative illustrations of animals in nature, but her legacy isn’t just her substantial contribution to the world of children’s literature. The fortune she subsequently amassed allowed her to purchase parcels of land — generally not an option to 19th century British women — to help preserve the beautiful English Lake District. Upon her death in 1943, Potter bequeathed her land holdings to the National Trust, and those became a sizable portion of what is now the Lake District National Park. In 2016, on the 150th anniversary of Potter’s birth, Chronicle Books commented that she was “far more than a 19th-century weekend painter. She was an artist of astonishing range.” Rather than showcasing one of her children’s book illustrations, we’re including several of the fungi paintings, which Potter created as a young woman, to exemplify the extent of her talent. These intricate watercolor specimens, which gained her respect in the field of mycology, are currently at the Armitt Museum and Library, Cumbria County in the Lake District. Composite of fungi watercolors, c. late 1890s, by Beatrix Potter (clockwise, top left): Lepiota friesii, Hygrocybe coccinea, Flammulina velutipes, and Hygrophorus puniceus Joan M. Rehlin

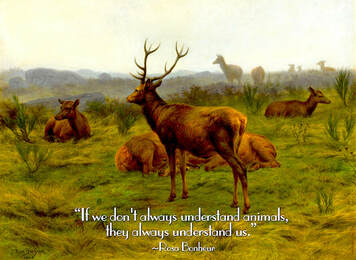

A mini art history post in celebration of Women's History Month 2019... Rosa (née Marie-Rosalie) Bonheur is considered the most famous female painter of the 19th century. During a time when it was difficult for women to receive an art education, Bonheur’s success opened doors for younger women artists. Bonheur (3/16/1822–5/25/1899) identified with the power and freedom reserved at that time for men, and as a result, she broke various boundaries which paved the way for other women. As an animalière (painter of animals), Bonheur gained international recognition during her lifetime and was best known for her artistic realism. Bonheur was born into a family of artists in Bordeaux, France, and moved to Paris in 1828. Unusual for that time, her parents believed in the equal education of women alongside men. As a child, Boneur had difficulty learning to read and write, and was taught by her mother to sketch a different creature for each letter of the alphabet. This led to Bonheur’s love of drawing animals, and she was encouraged by her father — a landscape and portrait painter — to paint alongside him in his studio where he brought live animals for her to study. She then furthered her training in animal anatomy at the National Veterinary Institute in Paris. Among Bonheur’s many credits are receiving a painting commission from the French government; having paintings in prominent exhibitions including the Paris Salon of 1848; being decorated with the French Legion of Honour by Empress Eugénie in 1865; and being promoted to Officer of the Order in 1894, the first female artist to receive this award. Nonetheless, Bonheur became more popular in England than her native France after she met Queen Victoria who admired her work. In addition, Bonheur exhibited globally, including at the Palace of Fine Arts and The Woman's Building at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, IL. Currently, Bonheur’s paintings are in New York City's Metropolitan Museum of Art and the collections of other important institutions worldwide. The Monarch of the Herd / Le Monarque de la Meute, oil on canvas, 1868, Rosa Bonheur Joan M. Rehlin

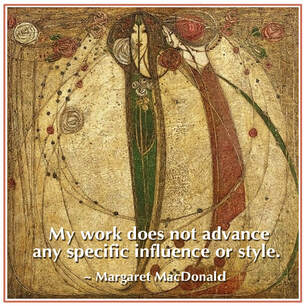

A mini art history post... Born in England, Margaret MacDonald (11/5/1864–1/7/1933) moved with her family to Scotland when she was 26. She and her sister, Frances, enrolled in the Glasgow School of Art and, in the 1890s, opened the MacDonald Sisters Studio in downtown Glasgow. While at the School of Art, MacDonald met Charles Rennie Mackintosh, whom she married on August 22, 1900, and the two of them formed an artistic collaboration that lasted throughout their lives. MacDonald’s well-known works are gesso panels, designed with Mackintosh, which were made for interiors in tearooms and private residences. Although Mackintosh is recognized as Scotland's most famous architect, with his wife being marginalized by comparison, MacDonald was nonetheless celebrated by many of her peers, including her husband. Mackintosh wrote to her, “Remember, you are half if not three-quarters in all my architectural work... .” He further stated that “Margaret has genius. I have only talent.” Between 1895 and 1924, MacDonald contributed to over 40 European and American exhibits including the 1900 Vienna Secession, where she was an influence on Gustav Klimt and other artists. Declining loyalty to any specific movement, she designed pieces which demonstrate an originality that distinguished MacDonald from her contemporaries. In 2008, MacDonald’s White Rose and Red Rose (shown here) was auctioned for 1.7 million UK pounds or $3.3 million. White Rose and Red Rose, gesso on hessian on glass, 1902, Margaret MacDonald As another year comes to a close, we wish everyone the very best this season has to offer and a peaceful, happy new year!

Our Season's Greetings, shared here, was created by Jim Rehlin using a photo of his Cardinals II / Garden Gate acrylic-on-canvas painting. Joan M. Rehlin

Our mini art history post highlights William Hogarth (11/10/1697–10/26/1764), an English painter and printmaker who was considered the most significant English artist of his generation. Born in London, Hogarth enjoyed sketching the city’s interesting street life characters, and he was apprenticed as an engraver of trade cards and other business products when he was a youngster. By the age of 23, he was a professional engraver. Later in life he was appointed Serjeant Painter, an honorable and lucrative position with the British monarchy. Influenced by French and Italian painters and engravers, Hogarth created work that ranged from realistic portraits to satirical caricatures. The latter were often mass-produced as prints during his lifetime, and dealt humorously with “modern moral subjects.” Most likely not a coincidence, Hogarth was reportedly a member of the Hellfire Club, the name given to secret groups established in Great Britain and Ireland in the 18th century. Group members were generally high-society individuals, often involved in religion and/or politics, who took part in socially perceived immoral acts. Hogarth was also a member of the Rose and Crown Club whose members included artists and art collectors. With a following among both the public and royalty, Hogarth’s subjects included some of the most noteworthy names in Georgian society. One of Hogarth’s many portraits (shown here) is significant because it depicts Hogarth’s friend and art patron, Mary Edwards. Hogarth and Edwards enjoyed a close friendship which was fruitful for Hogarth particularly from 1733 until her death in 1743, when she brought him commissions, including a portrait of her infant son, and referrals for other work. In return, Hogarth painted his complimentary Portrait of Miss Mary Edwards, which is currently in the Frick Collection art museum in New York City. Portrait of Miss Mary Edwards, oil on canvas, 1742, William Hogarth Joan M. Rehlin

This month's mini art history post features Fancisco José de Goya y Lucientes (3/30/1746–4/16/1828), a Spanish Romantic painter, portraitist, and printmaker. Goya was referred to as the last of the Old Masters and the first of the Moderns. As an artistic chronicler of history, Goya depicted many of his subject matters with a leaning toward political satire, and he was immensely successful during his lifetime. Born into a lower middle-class family, at age 14 Goya began studying painting. At age 18 he moved to Madrid and then Rome, where he continued his art education. Two of his paintings survive from that period, both dated 1771, and that same year Goya won second prize in a painting competition. He then returned to his family’s hometown of Zaragoza where he was hired to paint religious frescoes and, in 1773, married Josefa Bayeu. In 1777, Goya earned a commission from the Royal Tapestry Factory to create rococo tapestry cartoons (from cartone, Italian for a large sheet of paper used to prepare tapestry). Designing over 40 tapestries that decorated and insulated stone walls in the Spanish monarchs’ residencies, Goya parlayed that commission into more prestigious work. During the 1780s, he painted portraits of Spanish nobility as well as royalty, and he also earned a salaried position as painter to Charles III in 1786 and Charles IV in 1789. Many of those portraits are notable for their satirical, less-than-flattering portrayals. Shown here and currently in Madrid at the Museo del Prado, Charles IV of Spain and His Family is thought to reveal the corruption behind the king’s rule, with his wife, Louisa, having the real power. Goya placed her at the center of the group and, at the back left, placed himself looking out at the viewer. In 1793, an illness left Goya deaf and contributed to his being withdrawn. He may have also suffered from lead poisoning due to his using large amounts of lead oil paint. His subsequent physical and mental decline produced dark nightmare fantasies and caused a change in the direction of his work. At age 75, Goya painted a series of 14 Black Paintings in oil, directly onto the plaster walls of his home. Those remained relatively unknown until almost 50 years after Goya’s death when the works were removed and put on permanent display in the Museo del Prado. Charles IV of Spain and His Family, oil on canvas, 1800, Francisco Goya Joan M. Rehlin

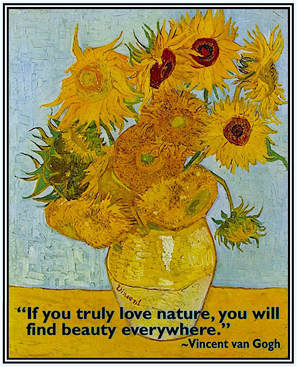

Our mini art history post highlights Dutch post-impressionist Vincent Willem van Gogh, whose painting style has had a significant influence on Jim’s artwork. Vincent van Gogh (3/30/1853–7/29/1890) is considered one of the most significant artists in the history of Western art. His use of bold colors and expressive brushwork contributed to the beginnings of modern art. Van Gogh created approximately 2,100 artworks in a little over 10 years, including 860 oil paintings with subjects ranging from landscapes to still lifes to portraits. As a child, Van Gogh demonstrated a talent for drawing, but as a young man he chose not to pursue this and instead worked as an art dealer. After a few years, he began experiencing depression and turned to religion, studying theology and working as a missionary. In his late 20s, Van Gogh returned to live with his parents and refocused his attention on art, painting peasant laborers and still lifes. In his early 30s, he moved to Paris and lived with his younger brother, Theo, who was a financial supporter and lifelong friend to Vincent. In Paris, Van Gogh met several influential members of the avant-garde, including Paul Gauguin, who were moving beyond impressionism to post-impressionism. Spending time in the south of France, particularly in Arles during 1888, Van Gogh honed his style and painted several series of artworks, including wheat fields and sunflowers. One of those — Still Life: Vase with Twelve Sunflowers (shown here) — is currently on display in the Neue Pinakothek Art Museum in Munich, Germany. While in Arles, Van Gogh’s mental and physical health continued to suffer, which resulted in his cutting off his left ear. In and out of treatment, he experienced severe episodes of mental instability, and in 1890 Vincent van Gogh shot himself and died a few days later. Van Gogh did not achieve recognition during his lifetime, but his works are now among the world’s most expensive paintings. In 1890, while Van Gogh’s work was on exhibit at Artistes Indépendants in Paris, Claude Monet said it was the best in the show. And as a prolific letter writer — to his brother Theo and sister Wil, as well as to Paul Gauguin and several other artists — Van Gogh’s words add a unique dimension and understanding to his artwork, not offered by other painters. Still Life: Vase with Twelve Sunflowers, oil on canvas (35.8” h x 28.3” w), 1888, Vincent van Gogh Joan M. Rehlin

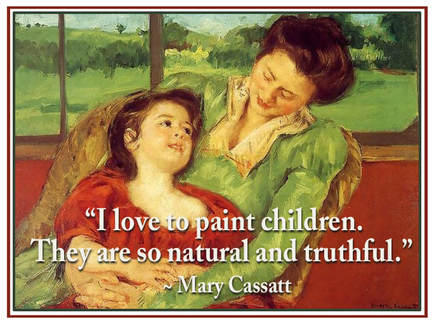

This month, which celebrates all mothers, is the perfect month to highlight Mary Stevenson Cassatt. Cassatt (5/22/1844–6/14/1926), who regarded herself as a figure painter, focused a large portion of her work on the intimate bonds between mothers and children. Cassatt was born in Allegheny City (now part of Pittsburgh) before moving with her family to Philadelphia. Cassatt’s mother, educated and socially active, had an important influence on her daughter’s artistic abilities. Cassatt traveled abroad with her mother and, at age 11, attended the Paris World Fair where she viewed the work of Edgar Degas, who later became a colleague and mentor. At age 15, Cassatt enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia, a prestigious institution that invited women artists to pursue their studies in its museum, paving the way for women to obtain formal art training. Cassatt moved to Paris in 1866 where she lived most of her adult life. She continued her studies through private instruction with masters from the École des Beaux-Arts. In 1868, one of her paintings was jury-selected for exhibition in the Paris Salon. Returning briefly to the States in 1870, she placed two paintings in a New York gallery, but even though the artwork had many admirers, neither was purchased. She returned to Europe in 1871, and was invited by Degas In 1877 to show her work with a group of artists who called themselves Impressionists. Exhibiting with the Impressionists, Cassatt used her share of the profits to purchase works by Degas and Claude Monet. Although she and the other female members of the Impressionists group were discouraged from meeting in Paris’ public cafés with the mostly male members, Cassatt enjoyed benefits provided by the wave of feminism during her lifetime, and she supported women’s suffrage. Beginning in 1887, Cassatt no longer identified herself with any art movement, experimenting instead with a variety of techniques. Cassatt was most prolific in oils and pastels. Her painting,Mère et enfant (shown here), is one of Cassatt's many renditions of motherhood. This work was exhibited in New York at the 1913 Armory Show, aka the International Exhibition of Modern Art. Mère et enfant (Reine Lefebre and Margot before a Window). oil, 1902, Mary Cassatt Joan M. Rehlin

As part of our promotional support of the national Prevention of Cruelty to Animals campaign, our April mini art history post highlights Thomas Gainsborough (5/14/1727–8/2/1788). Considered the primary British portraitist of the second half of the 18th century, Gainsborough is also recognized for his great love of dogs. Gainsborough’s affectionate artistic portrayal of dogs is in keeping with his advocating kindness toward animals, and he is attributed with encouraging people to see dogs as individual, sentient beings. Best known for portraits of people, e.g. “The Blue Boy” (1770), Gainsborough included dogs in many of his human portraits. In addition, he depicted dogs as the only subject in a number of artworks created on commission. And his “Tristram and Fox” painting (c. 1775) is a portrait of his wife’s and his two dogs, who were considered family members. Gainsborough’s father recognized his young son’s talent, and at the age of 13, Gainsborough was permitted to move to London to study art. In 1761, he began exhibiting paintings in what is now the Royal Society of Arts. In 1769, he was a founding member of the Royal Academy of Arts, and was an ongoing exhibitor at the institution which continues today to promote visual works of art through exhibitions and education. Gainsborough, an experimental as well as technically proficient artist, applied paint quickly in a style that combined poetic sensibility with his observations of nature. He preferred to paint landscapes over portraits, but because his portraits were more popular, in the 1770s he began depicting the subject in a landscape setting. The painting shown here is a lesser-known but, nonetheless, our favorite Gainsborough painting, and is hanging in the Duke of Buccleuch’s ancestral home. Henry Douglas-Scott 3rd Duke of Buccleuch, oil painting, c 1760, Thomas Gainsborough Along with promoting the artwork of Jim Rehlin and other artists, Rehlin Graphics / Fine Art supports animal rights. And as our poster (below) states, this month is Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Month.

To highlight this particular cause, we’re sharing a link to a website that lists some of the things people can do to help prevent animal cruelty, including making adoption your only choice when bringing home a four-legged friend. For more details, please visit the ASPCA website or their FB page. Then do whatever you can to prevent animal cruelty — not just this month, but every month — by speaking up and showing your support online and elsewhere. Artwork poster, below, created by Jim Rehlin who used his First Pack painting, changed the color to the monochrome shade of our RG / FA cover image, and then added the type. Joan M. Rehlin

In honor of Women's History Month, our March mini art history post highlights Lydia (Lilla) Cabot Perry. An American Impressionist painter who was influenced by the work of her mentor, Claude Monet, Perry (1/13/1848–2/28/1933) painted portraits and, to a lesser degree, landscapes. Although she created sketches at an early age, she received no formal artistic training until age 36 when she began taking lessons in Boston. In 1874, she married Thomas Sergeant Perry, and in 1887 when her husband’s career required a move to France, the family settled in Paris where she enrolled in the Académie Colarossi. Unlike the government-sanctioned École des Beaux Arts, the Académie Colarossi was more progressive and accepted female students. Between 1889 to 1909, Perry spent nine summers in Giverny, France, where she formed a friendship with Claude Monet whose impressionistic handling of color and light greatly inspired her work. In 1897, Perry moved with her husband to Japan where she found new inspiration for her creative process and developed a unique style that combined western and eastern traditions. Perry was dedicated not only to her own artistic evolution and career, but also to the careers of other artists. Her efforts enabled a new generation of women to stake their claim in the art world, and through her advocacy for the Impressionist movement in the United States, she helped American Impressionists, such as Mary Cassatt, to gain exposure and acceptance. Perry also furthered the American career of Claude Monet, by lecturing on his talents and showcasing his works, and she helped found the Guild of Boston Artists, which supported Impressionism as a respected artistic style in the United States. Beginning in the early 1890s, Perry’s Impressionist paintings won medals at important exhibitions in Boston, St. Louis, and San Francisco. Between 1894 and 1897, her work achieved international acclaim, including being exhibited in Paris at the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, Champ de Mars. The Green Hat, self-portrait, 1913, Lilla Cabot Perry Joan M. Rehlin

We’re celebrating Black History Month by highlighting Edward Mitchell Bannister in this mini art history post. Bannister (c. 11/1828–1/9/1901) was a prominent 19th century Canadian-American artist, who was born in New Brunswick and moved to New England in his early 20s. While living in Boston, Bannister initially used his artistic skills to tint daguerreotypes, which were introduced during the mid-1800s. He married in 1857, and in 1870, he and his wife settled in Providence, RI. Inspired by the works of the French Barbizon School of painters, Bannister's pastoral landscapes and seascapes emphasize mood and shadow. He became one of the well-known Tonalist artists, and several of Bannister’s paintings were selected for group exhibitions at the Boston Art Club and Museum. In 1876, Bannister won a bronze medal – the highest honor awarded to oil paintings – for his Under the Oaks at the Philadelphia Centennial, the country's first national art exhibition. In 1880, he was among the group of artists who founded the Providence Art Club to encourage art appreciation in their area, and the organization honored him with the title of Artist Laureate. A successful career artist, Bannister was described in A History of African-American Artists as “a professional artist who lived by his painting.” Although Bannister was dedicated to racial equality, rather than focus artistically on equal rights he created paintings that present universal harmony, spirituality, and liberty. During his lifetime, he was widely admired within the East Coast art world. Unfortunately, he lapsed into obscurity for nearly a century, for reasons associated mainly with racial prejudice. Then, beginning in the 1970s, Bannister’s work was again collected. He was also celebrated posthumously through a variety of cultural events including, in 1978, having the Rhode Island College dedicate its art gallery in Bannister’s name and exhibit his work. Bannister’s River Scene, shown here, is currently displayed in the Honolulu Museum of Art. River Scene, oil on canvas, 1883, Edward Mitchell Bannister Joan M. Rehlin

A mini art history post, featuring Louise Caroline Alberta (3/18/1848 – 12/3/1939) who was the sixth of eight children of Great Britain’s Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Although she was a prolific artist, because Princess Louise was also a female and member of the British royal family, her artwork remained largely unknown until recent years. At the behest of their father, Princess Louise and her siblings were taught strict, practical tasks such as cooking, farming, and carpentry. When Princess Louise demonstrated artistic talents, her mother allowed her to study at the National Art Training School. Yet, due to her royal rank the princess was not allowed to pursue an artistic career. Not to be deterred, the princess continued creating art, and when her husband. Lord Lorne, Duke of Argyll, was named Canada's Governor General, they moved to Ottawa’s Rideau Hall where Princess Louise hung her paintings and installed her sculpted works. While in Canada, they founded the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, and the princess continued creating artwork with a fondness for depicting scenery near their cottage on the Cascapedia River. Several of Princess Louise’s sculptured works remain standing today, including: 1) a statue of Queen Victoria in front of the Royal Victoria College, Montreal, now McGill University; and 2) one outside Kensington Palace where the magnificent statue, created to mark the Queen’s golden jubilee, both flatters as well as suggests the chilly nature of its subject. Due to increasing ill health, the last public appearance Princess Louise made was at the Home Arts and Industries Exhibition in 1937, two years before her death. Her passing, at age 91, left a wealth of artistic creations which include, clockwise from upper left: A View of Lake Como, watercolor, 1871 View from Lorne Cottage, watercolor, c. 1879 Queen Victoria, sculpture at Kensington Palace, 1893 Joan M. Rehlin

Another of our mini art history posts... Jean-Antoine Watteau (October 10, 1684–July 18, 1721), known as Antoine Watteau, was a French painter and one the leading Rococo artists of the 18th century. Watteau shifted the waning Baroque style to the less formally classical, more naturalistic, witty, and playful Rococo style, which is considered a major period in the development of European art. Although Watteau’s father expected his son to follow him into the construction field, Watteau showed an early talent in painting. At the age of 18, he moved to Paris where he found employment and honed his artistic talents at several studios, developing a style of drawing that was admired for its sophisticated elegance. Watteau’s major influences included Peter Paul Rubens’ series of elaborate canvases created for Queen Marie de Medici, as well as the work of the Venetian masters. Watteau was admitted to the French Academy and is credited with inventing the fêtes galantes genre, a term coined in 1717 by the Academy to describe Watteau’s bucolic, idyllic scenes that include a flair for the dramatic. Watteau’s paintings detail not only theatrical flamboyance but also a wistfulness regarding the transience of love and other earthly delights, a dichotomy Watteau understood all too well. Although surrounded by riches, coquetry, and elegance, Watteau didn’t partake of this charmed world due mostly to having contracted tuberculosis, the disease that took his life when he was only 36. More than most other 18th century artists, Watteau is celebrated now as having influenced every aspect of art during the Rococo period, including painting, costumes, interior design, plays, and music. Watteau’s The Feast of Love is currently in the Old Masters Gallery in Dresden, Germany. The Feast of Love, oil painting, c. 1718–1719, Jean-Antoine Watteau |

ART BLOGWelcome to our Art Blog where we occasionally present topics of interest in the fine art world, including featuring artists other than Jim Rehlin. Some of the artwork has been created by long-departed but well-known greats; some, by compelling contemporary artists. All will be pieces we find worthwhile to share with you. If you like any of these, consider sharing the posts forward to your own blogs and other social media. |

|

Artwork by Jim Rehlin.

Website content and modifications ©2024 Rehlin Graphics / Fine Art. All rights reserved. Click HERE to Visit and Like Rehlin Graphics / Fine Art on Facebook. THANKS! |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed